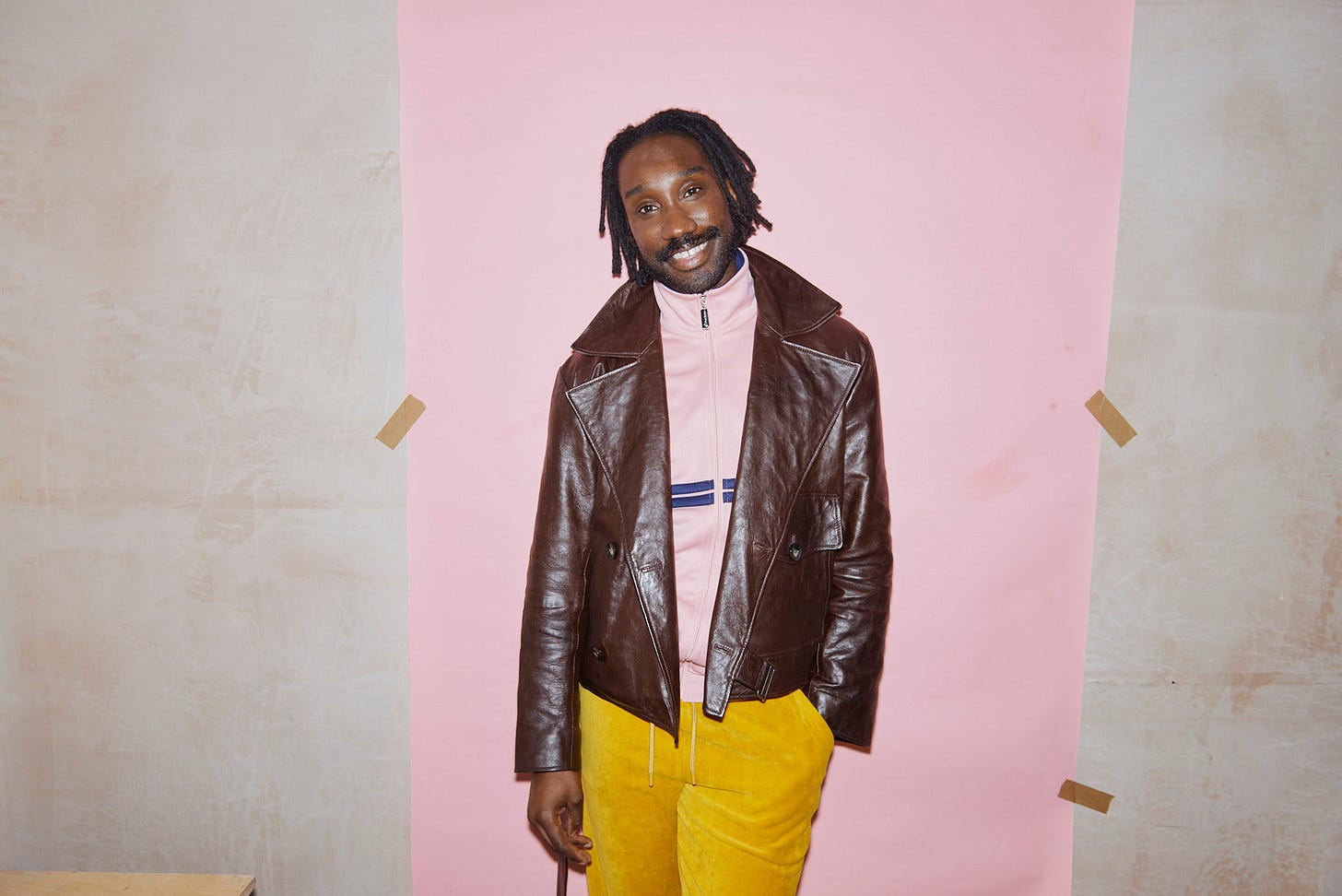

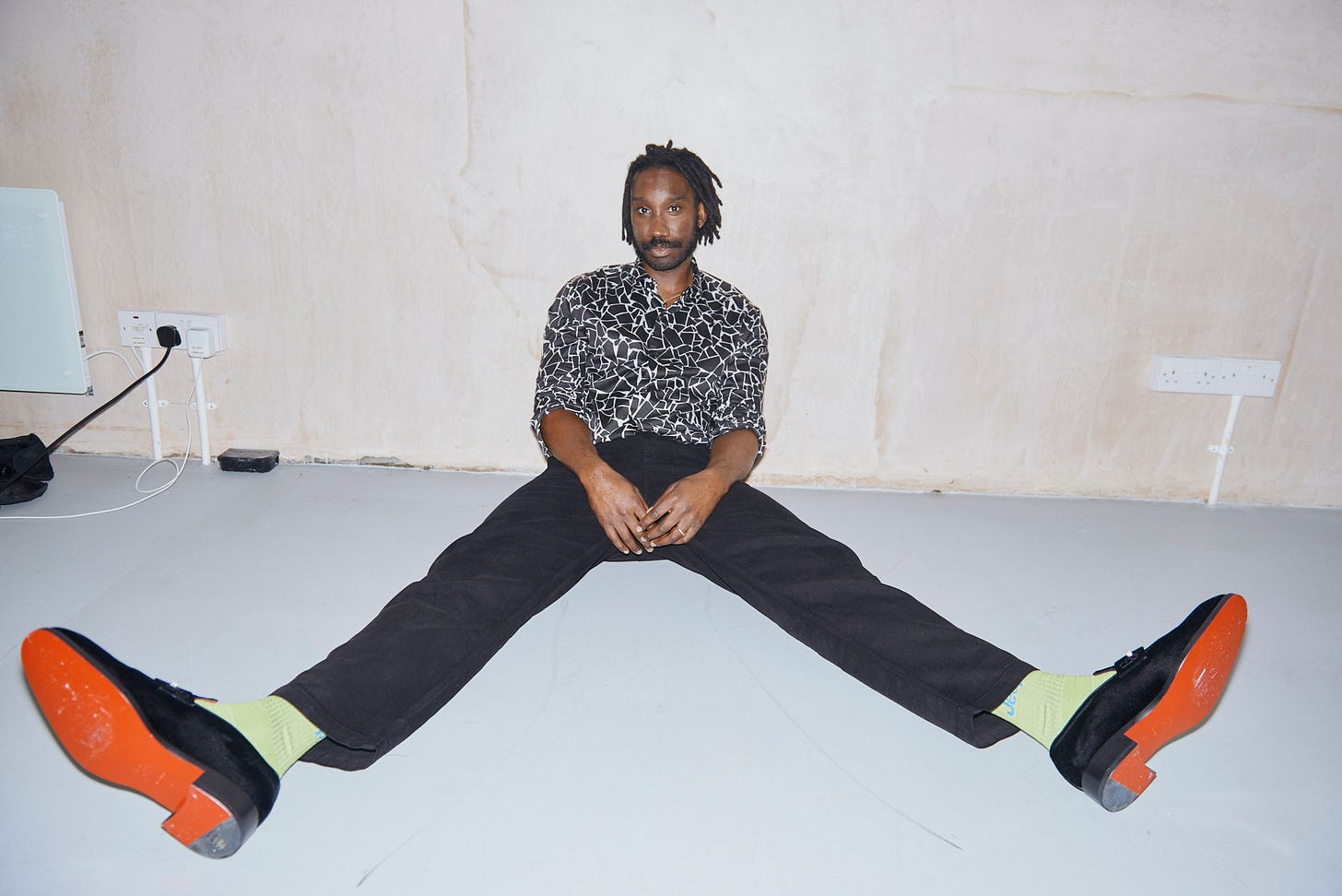

Nathan Stewart-Jarrett: The Man of Many Selves.

Nathan Stewart-Jarrett is a livewire presence: funny without trying, thoughtful without fuss, and possessed of the charming unpredictability that makes you wonder which version of him you’ll get next.

Interview - Perry Curties

Portraits - David Titlow

Styling - Lily Lam

Grooming - Nohelia Reyes using 111skin and Maria Nila

Fashion Assistants Theo James Elvis, Sasha Clegg

Shot exclusively for The 3rd Act at All Saints, London, November 2025.

Nathan Stewart-Jarrett arrives at our table in a very loud art gallery cafe, and for a moment, I’m genuinely not sure which version of him I’m about to shake hands with. In the last seven days I’ve watched him play the bruised but beguiling drag queen in Femme, the hysterically heightened Jack Worthing in The Importance of Being Earnest on stage in London’s West End, and the brooding, near-wordless enigma/anchor in Down Cemetery Road for Apple TV+. Usually, after a week spent bingeing someone’s work, you start to sense the person behind the performances — many actors in real life turn out to be perfectly aligned with the characters they play. But this guy’s recent roles are so wildly different that I find myself wondering: who exactly is Nathan Stewart-Jarrett?

He wonders it, too. “I think I’m in it all,” he says with a shrug. “Because it’s still me.”

And this is the peculiar magic of Nathan Stewart-Jarrett. He is not an actor who imposes a single persona on every project; nor is he a chameleon disappearing behind prosthetics and accents. Instead, he seems to stretch himself — amuse himself — by heightening certain facets in each role. He describes this with a kind of gleeful self-exposure.

“In comedy, I’ve amplified some of the worst bits of myself,” he says. “It’s probably the ugliest bit of myself that I’m putting out without even realising it.”

He says this like someone confessing to an innocent prank rather than an artistic strategy. Comedy, for him, is a place where he can be “petty, pithy or… [he cant think of anymore P words] things you’d want to do in life but you stop yourself.”

Anyone who’s seen him in Earnest might suspect some improvisation floating under the surface of the Wildean dialogue, but Stewart-Jarrett insists that’s an illusion. “No improvisation with lines,” he says. “It’s not allowed.” Wilde, after all, is practically holy text.

But delivery? That’s a different matter entirely.

“It changes every single evening,” he says. “Sometimes something happens, you just make each other laugh by mistake.”

He lights up as he recounts the live-wire unpredictability of theatre. There was the night that co-star Olly Alexander, shut his finger in a door mid-scene. “He was obviously in pain but I found it really funny.” Another evening, Alexander stood on his foot. “It really hurt, but that’s the joy of theatre. Mistakes are wonderful.”

At the mid point of a 3 month run had become, by then, a kind of shared hallucination — endlessly repeatable yet constantly mutating. “You’re a different person every day,” he says. “You find different ways of delivering the line. It means something different to you on a particular night.”

At one point we find ourselves discussing Laurence Olivier’s notorious meltdown backstage after a universally praised performance he feared he could never repeat.

Stewart-Jarrett nods. “You don’t really try to repeat or even perfect it” he says. “I really don’t want to get caught in that.”

On film, he’s learned to drop the idea of perfectibility altogether. Early in his career he’d keep pushing, tweaking, trying to adapt each take. It never worked.

“Now I call it polishing a turd,” he says cheerfully. “You get tighter and tighter. These days I just move on. Keep it loose.”

Given the spectrum of characters he plays, and duality of his town & country personas in his roles I ask whether there are multiple Nathans in real life too.

“Yeah, there are actually,” he says immediately.

“City Nathan is sharp, sociable, animated by restaurants, galleries, and the general hum of London or New York. Country Nathan is quieter: cooking, watching films, reading, wearing the same jumper for two days because “no one’s going to see you.”

For nearly a decade he’s lived in New York — which prompts a brief detour into a discussion about American wildlife. “In America, there’s wild animals,” he says with mock-gravity. “They’ll get you if you go for a walk in the country!”

So he prefers winter walks. Summer walks, especially in the countryside, feel like tempting fate, he smiles, “To be honest I become a slob in the country. Maybe that’s what you’re meant to do.”

Discussing his most significant roles, a pattern emerges: Stewart-Jarrett keeps playing more than one person at a time.

In Femme: two.

In Culprits: “I was actually three people in that.”

In Misfits (his early breakthrough role): his character eventually shape-shifted into a woman.

In Ernest the entire premise is dual identities.

Even in Cemetery Road it feels like two characters, given the mystery of the role in the first third of the series.

“Is this a theme?” he asks, amused. “Maybe I should have been a twin.”

But he has a theory. “What I often play in characters is secrets… someone with a secret life. It’s a great conceit. Those characters are incredibly interesting.”

Secrets, he believes, are the engine of narrative. “We all have them,” he says. And dramatically speaking, “a secret is a great tool.”

When the conversation turns to Femme, his face brightens.

“It was something really special,” he says. “We could all feel that at the time.”

The cast reunited recently in his dressing room during the Ernest run. “It was special to be back in one place with all of those people at once.”

He believes the film will grow in stature. “It’s got a life afterwards,” he says. And he’s proud of how it looks: the softness of the lighting, the unexpected colour palette. “London films are usually more grey,” he says. “They went for a different aesthetic.”

Now, though, the focus is on Apple TV+’s Down Cemetery Road, where he plays the enigmatic Downey — a man whose silence becomes its own form of exposition.

“I didn’t speak for the first couple of episodes,” he says. “It was weird until I realised… it was a gift.”

He had to unlearn the actor’s instinct to fill the space. “You feel like you have to impart all this stuff,” he says. “Then I was like, Well, shut up. Just be.”

Episode 5 — which he confirms is “a big one” — brings Downey’s past into focus, introducing a sister who never knew he existed and revealing the central storyline that he’s been hiding.

He absolutely won’t say what happens next. “It’s Apple! They’ll deliver a poison apple,” he jokes. “It’s a Snow White situation.”

But he clearly loved filming it — especially the Bonnie-and-Clyde-style bickering with his co-star. “Our massive argument in the car was so hilarious to film,” he says. “You really get to feel their bond.”

There’s action in Cemetery Road too, and Stewart-Jarrett, it becomes clear, is unexpectedly enthusiastic about stunts. This wasn’t always the case. He used to be terrified — too many military uncles, too much pressure to “get it right.” But a revelatory experience on Disney’s Culprits changed his mind.

“Once I got over it… once I got into the fun of it, it was like being a 10-year-old wrestling with my cousins again,” he says. “Those stunt days were some of the best days ever.”

“I’d love to do pure action,” he says without hesitation. Something Charlize Theron-esque. Or perhaps, judging by his enthusiasm, something in the John-Claude Van Damme oeuvre. There’s one film he can’t stop laughing about, where Van Damme plays a fashion designer. “It’s so ridiculous,” he says, delighted. “It’s so good.”

As we wrap up our conversation, we circle back to the contrasting worlds he occupies as an actor: action roles, romantic roles, and the relatively recent — and vital — presence of intimacy coordinators on set. I pose a ridiculous hypothetical dilemma: would he choose a stunt coordinator or an intimacy coordinator if a project only had the budget for one?

“On Femme, the intimacy coordinator was indispensable. We couldn’t have achieved what we achieved without Robbie Taylor Hunt,” he says. The role, he believes, is akin to having a mediator. “You have to establish trust: don’t touch this part of my body, you can touch all of my body, if I do this… whatever. A third party is really useful.”

Over time, he’s become confident in setting his own boundaries. “If I have to be naked alone, I can say to a director, ‘You have three takes. If you don’t get it by the third take, I’ll put my clothes back on.’”

He laughs. “But of course you absolutely can’t work without a stunt coordinator — unless you want to lose a leg!”

We’re getting up from the table now, so I throw him one last hypothetical: which classic film role would he take on if he could go back in time? He relishes the dilemma and cycles through options before landing on two comedies — Ryan O’Neal’s role in What’s Up, Doc? and Cary Grant’s in Bringing Up Baby. “They’re both uptight,” he says. “They make me laugh.”

Then, reconsidering: “Actually… I’d love to be Lestat. I’d make a really good vampire.” He grins. “A lazy vampire, but a good one.”

And perhaps that’s the perfect way to leave him: an actor who is, at once, many things — comic and tragic, physical and vulnerable, sharp and soft, seductive and silly; a man who delights in secrets, dualities, and roles that transform him. Over one week I’ve seen him inhabit three wildly different worlds, and yet sitting here, he somehow contains them all. Whoever Nathan Stewart-Jarrett becomes next — vampire, action hero, uptight screwball lead — it’s bound to be unexpected, and entirely him.

Down Cemetery Road is on Apple TV+ now.

Interview - Perry Curties

Portraits - David Titlow

Styling - Lily Lam

Grooming - Nohelia Reyes using 111skin and Maria Nila

Fashion Assistants Theo James Elvis, Sasha Clegg

Shot exclusively for The 3rd Act at All Saints, London, November 2025.